“Did You Hear What Eric Powell Done?”

New graphic novel from Goon creator Eric Powell matches his formidable skills with one of the foremost serial killer biographers to chronicle one of the most infamous crimes of mid-20th century America

It’s not an exaggeration to compare discovering the existence of Eric Powell’s new graphic novel “Did You Hear What Eddie Gein Done?”* (Albatross Funny Books, 2021) to stumbling onto some lost, you’d-somehow-never-heard-of-it ‘true crime’ comics artifact co-created by bestselling In Cold Blood novelist Truman Capote and premiere EC Comics artist Johnny Craig.

Both Capote and Craig were masters of their respective forms — and while Eric Powell’s artwork is often closer to Jack Davis in spirit and technique, it was Johnny Craig who was truly the master of mean, meticulous, measured, maximum-impact noir storytelling in EC’s horror and crime-suspense comics — as are veteran non-fiction serial killer expert/author Harold Schechter and Goon creator and multiple Eisner Award winner Eric Powell. Schechter and Powell are at the peak of their powers, and their collaboration on a graphic novel case history of the notorious Wisconsin necrophile/cannibal Ed Gein has borne a brilliant, insidious, terrible fruit. “Terrible” — in this company and context — is a compliment, as “Did You Hear What Eddie Gein Done?” (hereafter DYHWEGD) illuminates almost all the darkest aspects of Gein’s life, times, and crimes… those that Schechter knows of, in any case; and, if anyone still living in America today knows, it is Harold Schechter.

For the benefit of those comics readers and Eric Powell fans who’ve never heard of Harold Schechter, rest assured that this is the ultimate possible creative true-crime collaboration. A seasoned scholar and academic (Professor Emeritus at Queens College!) who has been writing sterling crime non-fiction and fiction since the late 1990s, Schechter launched his true-crime writing spree in 1998 with the back-to-back paperback publication of the definitive texts to date detailing the carnal appetites of Albert Fish (Deranged: The Shocking True Story of America’s Most Fiendish Killer!) and Ed Gein (Deviant: The Shocking True Story of the Original “Psycho”, the story of Ed Gein, the killer who inspired Psycho, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Silence of the Lambs). The latter title tells all, one might think, but 23 true-crime biographies, ten pop culture studies, seven academic texts, five mystery novels (eight, if we count Schechter’s collaborations with his daughter Lauren Oliver under the nom de plume H.C. Chester) later, Schechter matches Eric Powell’s zealous dissection of the Ed Gein life (and death) story with fresh insights and fictionalized (but grounded in fact) revelations new to even the most jaded Gein expert.

Prior to the 1998 publication of Schechter’s biography and case study for Pocket Books, Gein’s story had rarely been documented, though it had been repeatedly cannibalized in pop culture. Relegated initially to the crumbling pages of back issues of Life and various crime tabloids and true-crime magazines, as book-ended in DYHWEGD, it was Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel Psycho and especially Joseph Stefano and Alfred Hitchcock’s smash-hit theatrical film adaptation Psycho (1960) that spread the Gein legacy like a global contagion. Bloch, Stefano and Hitchcock transformed the real-life shy, soft-spoken, socially awkward closet deviant of 1950s Wisconsin and Bloch’s fictional overweight middle-aged motel proprietor (based, according to Bloch himself, in part on sf fan and Castle of Frankenstein editor/publisher Calvin T. Beck) into handsome, talkative boy-next-door Norman Bates, as embodied by Anthony Perkins in a career-making-and-shattering role.

That was how the archetype was fixed in amber throughout the 1960s in a procession of Psycho wannabes. But Monster Kids™ like me (born 1955) experienced all the ripple effects of the Gein crimes via the multiple incarnations that moved incrementally closer to the real-life Gein persona with each iteration. It was the double-whammy of Roberts Blossom (later beloved as Old Man Marley in Home Alone) as Ezra Cobb in Alan Ormsby and Jeff Gillen’s Deranged (opening March 1974, playing regional neighborhood theaters and drive-ins that spring and summer, which is how I saw it) and Gunnar Hansen as Leatherface in Kim Henkel and Tobe Hooper’s immortal The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (opening October 1974 and in constant circulation all through 1975) that shattered the ‘boy next door’ façade and propelled a far more primal and monstrous Gein surrogate into the zeitgeist. From there, it was initially the publication of David Schreiner’s article on Gein in underground publisher Kitchen Sink Press’s Weird Trips #2 (1978) — with an unforgettable William Stout Gein cover portrait (“Care to stay for some VITTLES?”) — that grounded the 1970s boogeyman Gein variant in Gein’s actual legacy. That was followed by writer Bill Kelley and artist Rick Veitch’s Harvey Kurtzman/Will Elder stylized Bazooka-Joe-meets-Ed-Gein “Momma’s Bwah!” in 50s Funnies (1980, under another glorious William Stout cover) and real-life Gein courtroom Judge Robert H. Gollmar’s regionally-published hardcover Edward Gein, America’s Most Bizarre Murderer (1981). Still, it wasn’t until Schechter’s 1998 Deviant that the Gein case was definitively documented for popular consumption, and it’s a measure of Powell’s dedication to co-creating the definitive Gein graphic novel account that he did whatever-it-took to forge an alliance with Schechter and bring DYHWEGD to print.

At this point in their respective careers, Schechter and Powell are both very polished storytellers, so it’s no surprise that DYHWEGD is an absolutely confident feat of both incisive biographical journalism in comics form and of unflinching, cut-to-the-marrow, no-nonsense, meat-and-potatoes graphic mayhem. Schechter and Powell showcase every perverse twist and turn of the Gein story, teasing out speculative biographical details of Ed’s childhood, adolescence, and adulthood under the tyrannical reign of his mother before the more gruesome procedural (and fully documented) minutiae of Ed’s atrocities. More tellingly, Schechter and Powell also detail the life of the Wisconsin environment and community that surrounded Gein — the very community he was shut away from, his struggles to interact culminating in what became his escalating procession of crimes against everything Ed’s neighbors and Eisenhower America took for granted — and individualize its citizens with clarity and warmth. Powell stretches himself throughout, and the payoffs, as and when they come, reward his steady-as-we-go application of stellar representational and expressive drawing skills and techniques.

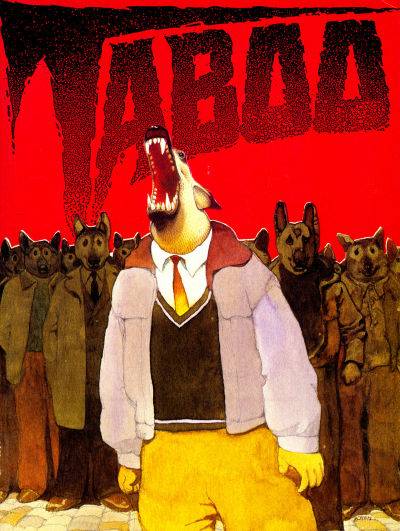

Perhaps due to the discipline of Schechter’s prose skills and ‘just the facts’ style, Powell practices uncharacteristic restraint and poise, carefully measuring his own delineation of events with a canny eye for characterization, place, time, and orchestration of excess (because the excesses are inevitable, and necessary). I’ve always adored Powell’s skill as an artist, but nothing prepared me for what he and Schechter accomplish here. Since I’ve cited by name their predecessors in the underground comix scene, it’s not a spoiler to note the occasional flourishes of speculation given full expression in DYHWEGD: the revelatory connection with an Aztec deity that echoes the late great Jack Jackson’s story “The Intruder” in Skull #1 (1970), which also echoes the at-the-time innovative way Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell breathtakingly illuminated the cosmic scope of the religious fervor that fueled the Jack the Ripper murders in a key single page of From Hell (“Chapter Two: A State of Darkness,” originally published in Taboo 3, 1989). Only now, it seems, has the graphic novel evolved sufficiently to grasp and communicate more than the depths of Gein’s depravities, but also that of his self-invented delusions and flesh-fueled faith.

I could go on and on (and will, elsewhere). Phil Balsman’s book design is impeccable and resonates with everything Powell brings to the table. Tracy Marsh lent vital editorial guidance to the process that is impossible to either recognize or properly acknowledge, given the seamlessness of the whole package. Suffice to note DYHWEGD is a sturdy and potent biographical work of true-crime graphic journalism that’s also a kick-ass horror graphic novel.

This isn’t for the squeamish — in case the uninitiated casual potential reader doesn’t recognize The Texas Chainsaw Massacre reference explicit on the front cover portrait, I’d advise said reader to turn over the book to see the trio of human-skin facemasks hanging on Gein’s wall (in the special edition of the book, as seen in many places online and in the banner here) — nor is it for the rabid gorehound seeking exploitative splattery thrills.

Schechter and Powell have lovingly executed their own Wisconsin Death Trip-informed retort to the delights of Rick Geary’s ongoing series of A Treasure of Victorian Murder graphic novels (which I absolutely love, BTW), responding to their own peculiar obsessions and archaeological digs into what might have made Ed Gein tick — and do what he done.

*quotation marks are part of the title

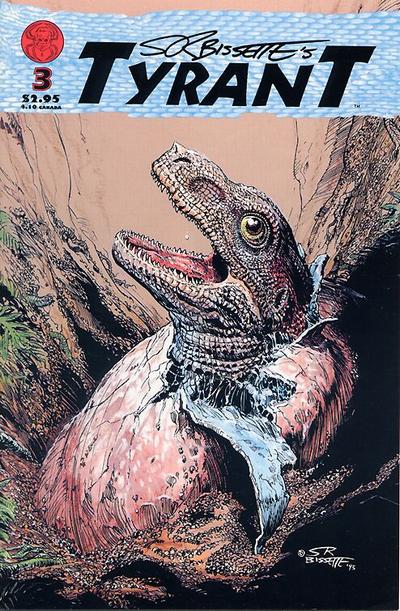

©2021 Stephen R. Bissette

Mountains of Madness, VT

Throwback vittles!

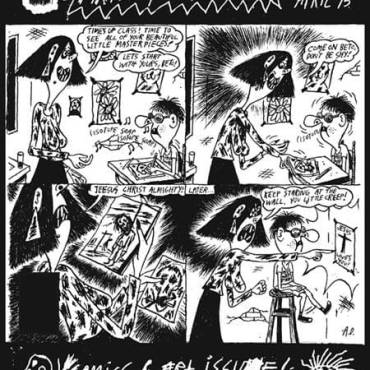

Stephen R. Bissette’s contribution to Mondo Howie #6, Wow Cool, 1991

Howie The Hat © & TM Wayno. Art Copyright © 1991 Stephen R. Bissette